The spiritual growth towards the divine

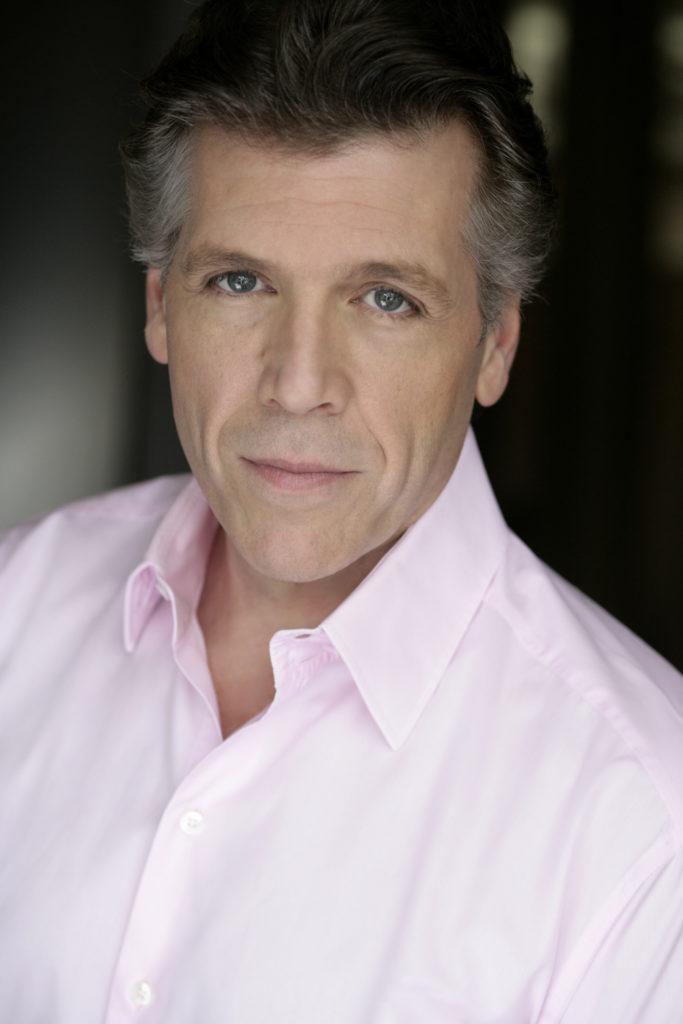

When I had the opportunity to interview Thomas Hampson in February 2001 on the occasion of his debut as Amfortas in Graham Vick’s production of Parsifal, he turned out to be a fan of Wieland Wagner’s take on Parsifal.

May I assume that today you are in the position where you can plan the career exactly as you wish?

With career plans it never goes the way you want, but it is true that within the repertoire I really want to sing, it is more a question of timing than whether I will ever sing certain roles. Where I work depends on impresarios and intendants, conductors and colleagues. The world does not revolve around Thomas Hampson. But I don’t sing anything I don’t wish to sing. I don’t sing anything that I don’t feel fully connected to for some reason. Either I have something to offer myself or I let the piece offer something through myself, or it is about an important dialogue that I want to be a part of, or I am simply shamelessly in love with the song, the opera or the role.

What is decisive in your decision to accept a particular role? Is it the state of the physical apparatus we call the voice or is it the maturity you think you need to interpret the role?

It is very difficult to separate the two things. I can’t think of an example where I could handle a role physically without being emotionally ready for it or vice versa. I’m very excited about my own development and I want to give myself as much space as possible to continue it. The next 10 to 15 years will be very interesting for me. I have reached the stage where my considerations of physical and emotional strength are now more a matter of whether the character I want to sing is what I want to put my energy into.

I have always been very careful about what I sing but the risk for me as a singer is not what I sing but how much I sing. You can make yourself very tired with too busy a schedule. I will never step out and sing something the way others think it should be sung. Furthermore, I make sure that my repertoire is very varied. Just recently I sang, for a month, 6 performances of Busoni’s Doktor Faust. If I were to sing exclusively that kind of repertoire I would not only be quite bored but it could also become very dangerous for me. With its extremely dark music, Faust is a very heavy opera for three hours.

In all this, do you consider yourself primarily a concert singer, a singer of the Lied repertoire?

Surely not. I do not make such distinctions for myself. Never will there come a time in my life when I will no longer sing songs. But neither will there be a time when I will not be on stage. I see both as complementary worlds and I keep both in balance very consciously. In the next 3 years I will find myself on the opera stage more than ever before in my life. What the music industry is doing with its division into lied-singers and opera singers is very dangerous especially for young singers. In the past, I never took on an opera role that could hurt my vocal abilities or take away my gift for singing Lieder.

Ten years ago, I received offers to sing Kurwenal. And then the big example is always: Fischer-Dieskau sang Kurwenal when he was 27 years old why can’t you? Well, I’m not Fischer-Dieskau. I probably could have sung it but who was waiting for that? There is a difference between singing a role and allowing a role to harm you. I don’t want to downgrade Dieskau’s incredible ability but the circumstances under which he did so no longer exist. The intendants, the orchestras, the opera houses are different. There are no 27-year-old Kurwenals today. And there is also Fischer-Dieskau’s self-proclaimed devotion to the Wagner repertoire throughout his young life. It didn’t harm his voice, not in the least. I think he was very concerned about that as we all are. But I am more concerned with achieving balance in my life.

This broad interest in repertoire, do you need it as an artist?

I think so. Once you’ve walked the tightrope of balance then people applaud and say: do it again! Because people really want to see how dangerous it can become for you. My repertoire is as eclectic as my mind. People have offered me so many incredible things such as recordings of songs by Chopin in Polish for Polish radio. Some musicologists sent me Romanian operas, Czech operas and incredibly obscure Russian pieces because people know that I dare to go to the margins of the repertoire. It challenges me, it fascinates me, and I also see it as a kind of responsibility to the musical world in general.

If you ask a random person on the street what classical music is you will not only be amazed at the amusing ignorance on the subject but you will also observe a rather disturbing indifference. This is not meant as a criticism, I rather see it as an interesting dialogue. If you took classical music off the radio stations you would only get surprised reactions. It is not the repertoire itself that we have done away with but the dialogue between the modern and the classical. The rejuvenation of that dialogue interests me. But turning it into a market or a repertoire is the worst thing we can do.

What is the challenge for you to sing the role of Amfortas in Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, a work many people are uncomfortable with? First of all, Wagner seems to connect eroticism with sin. Then there is the presence of all sorts of Christian symbols, and although there are good arguments for saying that Parsifal is not a Christian work, quite a few people believe that it is a very reactionary piece.

This is a dialogue that will drag on for years to come. It’s also an interesting dialogue and it’s important that there are essays written, for example, that believe that anti-Semitic themes are found in the second act. If that is true then we should perform Parsifal as often as possible to understand where that hatred comes from. Personally, I don’t notice any of that. I have yet to find a layer in Parsifal from which I must admit that Wagner enters into a personal dialogue with the world to attack the Jews or to proclaim Christian ideas. But I understand where those digressions come from: after all, whenever a work of art is so inescapably and deeply intertwined with symbol, metaphor and reality, there will continue to be room for comprehensive and dangerous dialogue. Whether it is Parsifal, Tristan or Tannhäuser, with regard to guilt and eroticism, Wagner was trying to get the dialogue back on track regarding the opposing polarities of our lives: our innate desire for the divine and our inability as human beings to ever transcend our death. This sets off tremendous thinking. It does not mean that there is a ready answer. It means questions are being asked. It means there is a thought process that we all have to participate in. And Amfortas to me is a kind of “Jedermann”: a metaphor for the human being who suffers from disharmony through guilt, which everyone can emulate

But why is having sex with Kundry a failure for Amfortas?

It’s not about the sex act at all. It would sound very banal if Wagner said “overcome the sexual urge”. Wagner could not do it himself and none of us can overcome it; it is an urge that is part of our lives.

But in Parsifal does Wagner try to teach us to overcome that sexual urge?

No, he is trying to bring balance to it. If you abandon your discipline to give freedom to your sexual drive then that is as much a failure with respect to your life as abandoning the sexual to engage only in that which you think represents the divine. If your life is preoccupied with breaking out of all sorts of conventions to find the inspiration of the artistic, which is essentially what Tannhäuser is about, then you encounter a dialogue that continues into Tristan and into Parsifal and is very much inherent in our existence.

Not long ago you had the generation that forbade its children to listen to jazz because it would affect the mind. Today we can laugh at that but I understand the generation that was terrified of that. I know my own reaction regarding rap music…. I find it horrible and rap doesn’t even bother me as much as techno. None of this would exist if there were no order. There will always be anarchistic attempts, emotional as well as physical, because of the existence of order. The fundamental walk of life is continuity but at the same time it seems to me that the fundamental impulse of life is also to look out for what challenges that continuity. So you get complementary equilibria, it is the north and south pole of a magnet that gives us the power to move forward.

And Wagner does not say : do away with all sex, nor does he say live like a celibate monk, but you cannot abolish your own destiny.

Yet Parsifal is a work that touches on religion. It is the only work in opera literature that has such ambition. Wagner therefore called it a Bühnenweihfestspiel….

It has nothing to do with religion, but it does have to do with spirituality. The Magic Flute does the same thing, you could also call it a “Bühnenweihfestspiel.” I make a clear distinction between concepts such as religion, spirituality and the divine. For me, the spiritual path is the only path that can bring the divine into one’s life. I think Wagner made a tremendous effort in that area. Through a phenomenal skill in screening the failures of our religions, he reminds us what spirituality is, and in the most inspired moments of some of his plays, he actually sheds light on the divine. And Parsifal is such a play: it will always be considered a “religious” work because people are consciously or unconsciously brought to a new spiritual dimension in their lives through it. But where I think it is not a religious work is that I don’t think it is guilty of proselytism.

We should not immediately interpret the word Christ as Jesus. Christ is a Greek word meaning “the chosen one.” It is a symbol from Judeo-Christian ethics and there have been many Christ figures in many religions and in pagan philosophy. The Christ figure is reflected in Parsifal but that does not mean it is a Christian work. The influence of the self-proclaimed atheist Schopenhauer is much greater. Schopenhauer gave us some of the most important spiritual writings of the 19th century and I think we need to understand that before we take Wagner at his own words. By the way, I don’t think the great composers showed an intrusive zeal for conversion. They opened a dialogue that helps you find your own way. I don’t think Wagner wants to show the way in Parsifal, just the opposite is my feeling. He leaves a lot of doors open and you have to find out for yourself that there are Kundrys and Amfortases walking around in the world and that they are both unbalanced people.

That brings us into the realm of the Grail. What is the Grail? Is the Grail a real object or is it a metaphor or is it a symbol?

I myself am very influenced by Wieland Wagner’s interpretation of Parsifal. It is an intelligent and very beautiful reading of the work. I indeed believe that the spear and the chalice belong together and that the Grail is the harmony of these two opposing elements in one’s life. In this Parsifal you have Graham Vick having Kundry die at the end after she is blessed by the archangel. But does she really die? The whole idea of mortality and immortality is connected to the concept of transcendence. We transcend when we die. That’s why you can’t read biblical literature too literally because dying doesn’t always mean it’s over. It can also mean spiritual rebirth. Armed with such metaphors and symbols, you must go to Parsifal to find your own path….

Wagner said, Amfortas is my Tristan of the third act but unimaginably intensified. How do you intend to build up such intensity?

That is impossible to do. You have to believe in it. How can you prepare yourself for something like that? Orson Welles said “the biggest roles are also the shortest because the rest of the cast is standing around chatting about you all night.” And then you finally get on stage. It’s a bit like that in Parsifal, the whole evening is about Amfortas’ dilemma. The scenes I sing are in fact very short but the moment Amfortas appears on stage and is dragged onto the stage, as it were, he brings with him the whole of human history and this rupture of what should have been the undivided path to the divine. He is a metaphor for our own failure to find the spiritual path to the divine. All you can do is let that knowledge act on your own body. You have a physically bleeding wound, and at first I thought it was strange that Graham Vick wanted to stick some kind of abscess on me. But in fact that makes a lot of sense, the wound is not just a metaphor, it is physical, there is a cut. There is also the reference to the wound of Jesus. So I don’t deny the connection with Jesus but it’s just one of many connections.

Do you think there is a great future ahead for opera as an art form?

Undoubtedly. Whether the canonical works of opera literature still have an expansive future, I don’t know. People have always sung to each other and have always told stories and produced plays. It’s an instinct that is inherent in our lives and won’t just disappear. Our conceited generation thinks it is damn smart, that it has understood all of history and can rush into the future as if it knows exactly where it is going to end up. It would be very illogical to claim that opera will disappear. Opera will certainly mutate, it will certainly take other forms. This is already visible in America through other forms of musical theater. When Mahler, Stravinsky and Schoenberg put people speaking and singing in the middle of a symphony you were also told that this must be the end of the symphonic form. I think it’s a very exciting time to be alive.

Is this time also exciting for the singer-actor? How do you experience the relationship between the director and the singer-actor?

A director has the responsibility to make their own inspiration arise in an actor. It’s a kind of balance and you can quickly see which of the two is the most inspired. Opera is different from the spoken theatre in the sense that the framework of the play is already established by the musical structure. What I have problems with are theater directors who don’t understand the role of music within the framework of the play. We come from a period where directors have sometimes lacked confidence in the music. When Amfortas begins with “Wehe! Wehe mir der Qual! Mein Vater, oh! Noch einmal verrichte du das Amt!”, then you get these 8 bars of sequential triads in the accompanied recitative. It’s difficult to sing because I have to lead the orchestra in the development of the harmony. It’s an accompanied recitative that comes straight from Mozart and even Monteverdi and is carried over Bach to its highest form. It is a most amazing musical structure and there is nothing I can add to it as a stage actor. That’s the difference between opera and a play, and a director who doesn’t understand that gets into trouble. But it’s a fascinating dialogue. The singing actor is someone who engages stagewise as much as he can but who is also guided by other cues. Those triads are there for a reason.