An Interview with Thomas Hampson

culturekiosque | By Joseph E. Romero

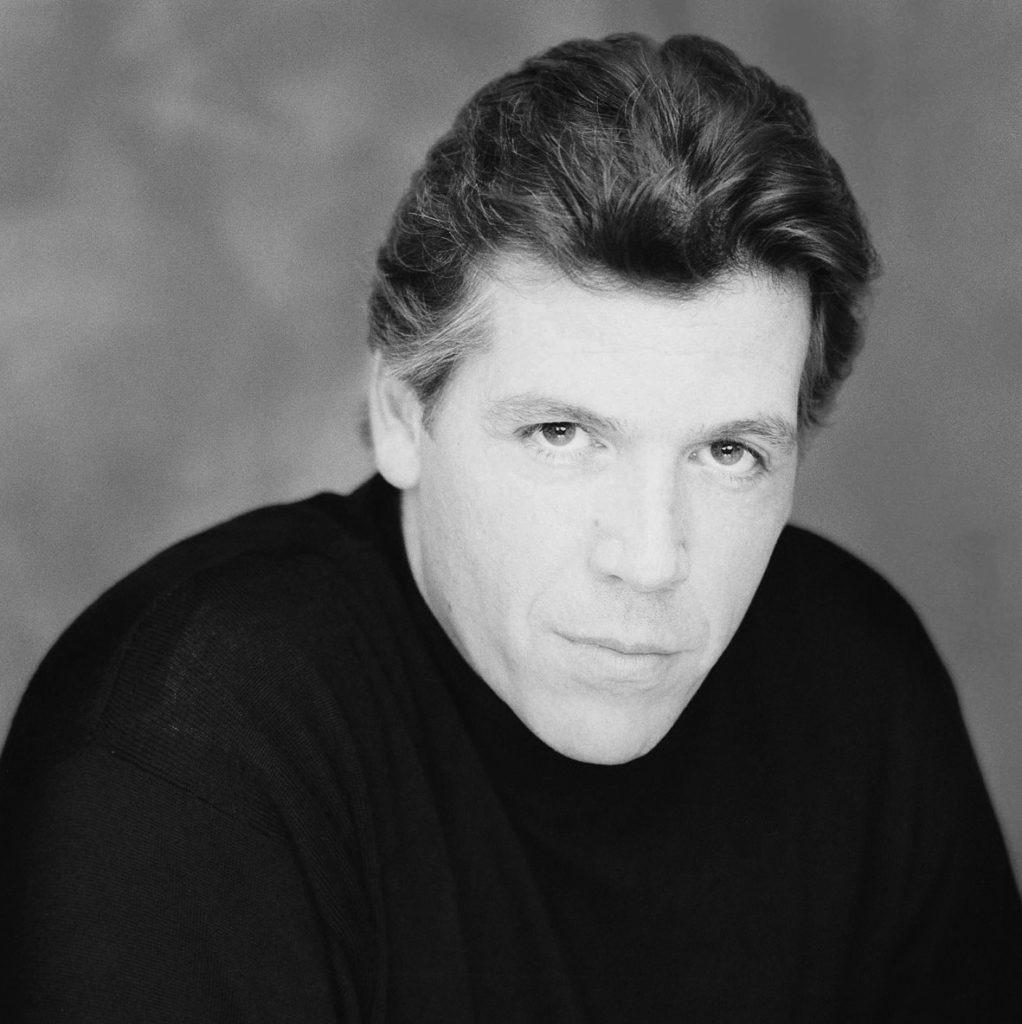

PARIS, 10 JUNE 1998 — The Indiana-born baritone Thomas Hampson has carved out a mighty career in ten years, regarded in some circles as a successor to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau for his mastery of a wide repertory to which he is drawn by an intellectual curiosity of astonishing breadth, as his program notes and website indicate. Equally at home on the opera stage – where his Onegin and Hamlet have mesmerized audiences – and the recital platform – where his Schubert, Schumann and Mahler interpretations are among the best today – Hampson is an artist at the peak of his powers.

He is also a big man. At 6’4″ and 230 lbs., the 42-year-old baritone from Washington resembles more America’s recent generation of offensive linemen than an international opera star. Loquacious with a warm manner, Hampson likes a good laugh and has strong opinions about everyone and everything from 19th century German poets to President Clinton’s politics on race.

Klassiknet’s Joseph Romero interviewed Thomas Hampson shortly before the season’s final performance of Eugene Onegin at the Opéra Bastille in Paris.

JR: How long have you been surfing on the Net?

TH: Probably two and a half years. My kids are very active in it. My oldest step-daughter is hugely computer-active.

JR: Why did you create a website?

TH: I’m a a computer nut and a Macintosh freak. I am also busy with various multimedia projects with broadcast companies like NPR, WNET or PBS. We deal with a lot of cross-discipline efforts to articulate the history of song, opera, poetry, theater, etc., and it made perfect sense to me.

The first reason I actually came up with a website was not necessarily to give information about Thomas Hampson, but to do back-up of recordings, so that somebody could actually listen to a recording and get more information than can fit in those stupid little CD booklets: all those solo projects that I do are real labours of love and are like children of mine. I do so much research for the sheer fun and enjoyment, that it would be nice to put up a time line or a different set of notes, different cross-references to poets and composers that someone could access while listening to the album, or scan in the music itself. It was also a means to tie ends together or link to different sites.

My site is divided into fan information and accurate schedule information which has replaced having to fax information all over the world.

The third site area is called the Conservatory where I keep articles I’ve written or that have been written about me, interviews and a planned book-shelf for book reviews of the humanities and singing, etc. I think there is a genuine desire on the part of the public to have serious and direct contact with an artist. I enjoy speaking to people and talking about what I do. The arts are a lot more accessible than a lot of people try to make them seem. I think it’s all part of our “software”. I wanted to find a way to tie more things together and be more accessible than just the hustle or advertising of Tom Hampson’s stuff.

JR: Anne Sinclair, one of France’s leading television and political journalists; interviewed Bill Gates not too long ago and asked whether Microsoft was interested in culture. While we do not know how the translater interpreted this question, Gates answered that Microsoft was very interested in “entertainment” which to the French is a bit like replying Burger King when someone asked you for the name of your favourite chef. What dangers for the future of your profession do you see in such an attitude?

TH: I think the danger is endemic to the entire culture. I don’t think it is just about my profession, especially since the Internet is now upon us. We are in a time where dollars, French francs or whatever are getting shorter for cultural events and also because we are seeing tremendous pressure on cultural events to become market-viable like entertainment events. We are seeing a stronger dialogue as to what is the difference between a cultural or artistic event and something that is entertainment.

Cultural and artistic events can be entertaining. If you go to the Louvre there is something terrifically entertaining about that experience. However, what you are going to see is an iconography of our passions, of our existence, our telling of the tale to other human beings before and after us as to why we exist. Sometimes, that is in a vernacular such as in entertainment, but more often than not it is a serious use of symbols, language, poetry and visual arts, and that has more to do with artistic events.

I think we have to recognize that the two are very separate. If we call the arts, classical music, the “cool” or “high end” of the entertainment industry, we are in fact abrogating the very reason classical music is something quite extraordinary or different or the reason why music is written in that vein or at that time. However, if you say that Paul McCartney or Elvis Presley is just shit, it’s just popular culture and it doesn’t mean anything, you’re missing the point of an artistic event.

The danger that is specific to us as singers is that if it is just entertainment, then the only regulating source is ticket viability. If it sells then it must be what the people want, it must be entertaining, it must be therefore artistic. If it doesn’t sell we can’t really support that because it’s not viable, it is not accessible to the people. They are not going to participate in it. The only way you can maintain that is by the lowest common denominator via a continual dumbing down by people who are assuming because of higher numbers that they are getting it right! If everything is based only on sales and ticket viablity we are in for some very serious problems in any notion of tradition and quality. It is not to say that one thing is better than another. That is the key to get off this polemic and start talking about what it is we are trying to express.

JR: With the arrival of major media groups on the Internet and their fusion with search engines, push technologies and other Internet traffic cops, there seems to be a repeat performance of what already exists in main-stream media, notably that entertainment is the preferred form of culture on the net. Celebrity news often dominates culture headlines on the Internet.

TH: The joy of the net is the ability to tie several different places together and gather several types of information quickly about what it is I want to spend a lot of my free time and my passion in developing. At other times I want to find other sources of books, tapes, video or audio events. That’s a huge plus of the Net. I think that you can have both. The amount of information is unlimited, but you will have a better audience if it is quick and you get through to what it is you are after very quickly. That should not have any effect on the quality of it, which is of course different from prime-time news on television. There, they do feel they have a responsibility to say it in a certain way because otherwise nobody will understand it. I don’t think we have to deal with that on the Net.

JR: How do you think internet technology can most benefit the performing and visual arts?

TH: Again, not only advertising on the Net of the different events is important, but the Net is a wonderful platform, especially in the arts, to tie in the various interdisciplinary efforts that make any one particular art viable. In other words, if it is about a museum or paintings there is a whole bunch of information on history, music and sociology. The same is true of opera. Opera is fascinating because it is such an amalgamation of such strong individual disciplines that unite in one three-hour period on stage, that it is just overwhelming. You can tell that story easier in an Internet environment than you can in a coffee-table book. Plus, it is also a hell of a lot cheaper.

JR: Today, there seems to be greater independence culturally in North America. Some European culture writers feel that Americans are fleeing into the future and view European culture in the same terms as those of an archaeologist studying the cultures and civilisations of antiquity. On the other hand, we see a greater number of American artists such as yourself performing in Europe. Do you see yourself as an archaeologist?

TH: [big laugh] What a question! That is a very nice way of talking about the Disneyland complex of Americans. There is a certain validity in it. You have stood by and watched as the tour buses empty out and somebody says “Oh, my God they do have flower boxes” as they are going through Austria. Some of that is inevitable, because of an American sense of history. While we have an almost egocentric belief in our position in the history of civilisation, we are nevertheless not told or can’t participate in it because if you are raised almost anywhere in the United States, anything older than 200 years doesn’t have a physical meaning to us. It isn’t there. It becomes our European forefathers. Some of what happens is an overreaction. We should talk about that more. When it isn’t talked about, it falls into the camp of cliché and impression.

I don’t feel myself an archaeologist in the least. I chuckle because archaeology happens to be one of my huge hobbies and passions. There is a certain archaeological aspect to what I do in reconstructing the circumstances from which either a theatrical event was born or an opera was composed, but more specially the hot-bed of fermenting personal, political and historical context that gave us romanticism in the 19th century or Sturm und Drang at the turn of the 18th century, or Classicism and the Enlightenment? Why did we need an Enlightenment? Were we a bunch of idiots before? Why the Renaissance? Why rebirth? What was dead? What needed to be reborn? All these contexts are something we flit by with these cliché-ridden marketing terms and they don’t necessarily hit us right in our solar plexus. If you are talking about Heine, you are not talking about some guy with talking flowers and tweeting birds. You are talking about one of the most explosive expressions of the human being in the first person in poetry that has ever been or ever will be. Without Heinrich Heine, Jack Karouac could sit on a coffee cup and say nothing. It just wouldn’t have happened. In the same way, without Wagner we would not have had Delius or without those two boys we wouldn’t have had jazz.

JR: Really?

TH: Of course, we would have had jazz. It would have been a different avenue. Those are our avenues. Go down them. Listen to it. Have an interesting relationship with it. Let it be your boulevard. That is what bothers me so much about this polemic with art or popular culture.

Criticism used to be a dialogue. It has now become a table of weights and measures that you stack up. How high can you hit the gong. That pyramid mentality has no place in artistic endeavor as far as I’m concerned. What is the best? Who is the one? Bullshit! It just doesn’t exist. I don’t think this dialogue is the road we should go down—-at all.

JR: You have given strong emphasis to American song. Has the day finally arrived when international audiences, notably Americans, consider American song composers as important as 19th century European song writers?

TH: Well it would be nice. My passion is song in general. I am passionate about poetry–as a diary of the human experience through various epochs. I revel in that and I think that certainly if you look at it in that rather wide context you have to see the dearth of effort in American song and ask yourself why has this been? And then you realize that it is because the system of weights and measures did not think it was very important. On the other hand, you start reading just below the surface of literature of people that we revere and adore as Americans: the English school. You realize that none of them, Stanford, Vaughan-Williams, Elgar, Delius, would have done what they did had it not been for Walt Whitman. It’s like Schoenberg saying that the most significant artistic influence on his life was Richard Dehmel, one of the great poets of the turn of the century. So, I think that dialogue is what interests me enormously. It carries over to the American side. Yes, I do sing a great deal of mid-century European song. I love the poetry of Heinrich Heine, but these people did not live in a vacuum. The last book that Schubert was reading was by James Fennimore Cooper. The American Transcendentalists were influenced by and had a reverse influence towards the French symbolists, towards the Yeats school in England. There has been a huge artistic dialogue that we haven’t paid attention to.

It is time for American music to unapologetically have a look at its past, especially as significant a 20th century as we have in American classical music. The avant-garde is happening in America: young composers, my generation, in their 40s and early 50s, and even younger. We are in a heyday.

JR: For example?

TH: Well, I think Richard Danielpour, Jake Heggie, a young guy out in San Francisco, Conrad Susa. Before that, you have some of the deans like Carlisle Floyd, hugely important man who didn’t get his due. One of the great renaissances of the next ten years will probably be Virgil Thomson. It’s time we finally gave Samuel Barber his due. He died a tormented and disappointed man. This breaks my heart, and I think, without any naiveté, involved one can hold Samuel Barber up in the tradition of song starting from Mozart up until our time and say that he is one of the major song writers of any culture, but yes he is American. Does that make him less interesting or less viable?

JR: Your rendition of Siegmund’s aria from Die Walküre on a recital disc caused a stir in certain circles, some suggesting that you are a lazy tenor. Is there any part of the Wagnerian repertoire that you would consider performing?

TH: Do you know what the real definition of a lazy tenor is?

JR: No

TH: A very rich baritone!

JR: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau recorded selected roles but never performed them on stage. Is that part of your recording strategy?

TH: I would never sing on record something I wouldn’t or couldn’t sing on stage. There isn’t enough time to do all the stage projects that I would like to do. I can’t imagine taking the time to do a La Favorite or a Don Sebastien of Donizetti or a Lucia di Lammermoor, quite frankly, or a Carmen Escamillo, but if somebody came with an interesting project for any of those roles, and if I could, I would love to do it. I can learn quickly. I can imbibe and ingest those roles. I know the repertoire very widely. The Siegmund thing caused a stir and it was a rather audacious and kind of a funny thing to do. I absolutely can sing the role of Siegmund. But if you start singing that repertoire, you can’t maintain Siegmund, Posa, Dichterliebe and Winterreise in your repertoire. As a singer, you can sing all of those things, but not at the same time. If I start singing things like Siegmund, Parsifal or Idomeneo, some of these lower tenor roles that I probably could achieve, I would have to refine or redefine my vocal technique a bit. That could build a certain inflexibility in my voice as a voice. As an instrument that would perhaps limit the subtleties necessary for the more serious effort that I want to make in 19th and 20th century song repertoire.

The other side of the Siegmund question: when the aria Winterstürme was published it had two different call numbers: one for tenor and one for baritone. I have both copies of that aria in those two call numbers and they are exactly the same music. That amused me. So, I thought I would call a few people’s bluff and throw it out there. It would not surprise me and I am not announcing plans for it, but it would not surprise me in the least to be offered in somebody’s next Ring Cycle the opportunity to sing Siegmund. The idea of changing to tenor is not in my consciousness at all, or starting to sing tenor roles. For one thing, the roles that I could sing we have plenty of tenors that can sing them. We need the guys that can sing the Siegfrieds and the Tannhausers and who can eventually develop into the Tristans.

We need two things: we need a little more reasonable realisation of what the 19th century aesthetic was and get off some of our young tenors’ backs and let them sing their roles lyrically like they should be sung. Secondly, we need to let young singers develop. I think the right to mature is the most endangered right we have in the classical singing world today. We want to get them at seventeen and call them “great” and “finished”. We want to get them at twenty-five and say, “well this is whoever it is”. I can give you names, but that would seem like I’m being nasty and I’m not. There is not one of these wonderfully talented people at twenty-five or thirty the same way I was. I wasn’t as “hot” a property. Nor was the world ready for doing the kind of thing they are doing today. When I was thirty and Lenny came along and I did the Vienna Philharmonic stuff, it was a big deal and I had a great career, but there was still the notion, especially from the big opera houses and the major presenters who were musicians who knew what they were talking about and people like Lenny [Bernstein] or [Jean-Pierre] Ponnelle who were really controlling and running the business, that “yeah this is terrific and he’s a wonderful thirty-year-old baritone and gee guess what, when he’s forty-five this is going to be really something special. We forget that Birgit Nilsson became THE Birgit Nilsson when she was forty-one or so. Some girl comes out now and she’s thirty or thirty-one years old and makes a big sound and everybody says “Oh you should do the Birgit Nilsson ‘fach’.” This is horribly unfair. As a singer and someone who does know the different schools of technique and has, I think, a firm grasp as a singer on the history of different kinds of singers, it is something I do intend to write more about. I think we have some serious reasons to let people mature.

Cecilia Bartoli is wonderful. She’s absolutely a delight as a colleague. I buy her records. I love them, but I wouldn’t want to say anything about Cecilia Bartoli, that what she’s going to be in twenty years is even going to be more interesting, more seasoned.

JR: Among all the lieder you have sung the number of French mélodies has been very small, is this an area that you have been avoiding and, if so, why?

TH: I am not avoiding it. In fact, stay tuned. There is only so much I can do. There are some great plans in the works. It’s a huge body of repertoire that I adore.

JR: Where do you stand on the topic of controversial productions by directors such as Robert Wilson (Magic Flute, Pelléas, Lohengrin) and Peter Sellars (Rake’s Progress or Pelléas, or Cosi fan tutte in a diner and Don Giovanni in Harlem where Don Giovanni shoots up during the champagne aria). Are there certain directors you do not care to work with? What do you do when you find yourself in a production you don’t believe in?

TH: [big laugh] I’ve got to get ready for tonight’s performance!

I am as open-minded a person as anybody. I always want to be responsible, to be part of an innovative or new thought process as much as anybody else and I want to work with some of these men who I consider to be extremely bright people like Peter Sellars or Robert Wilson. But, my own particular passion and belief is that I don’t think you should ever tell a story that isn’t the story we’re telling. I think sometimes we all get, and this can happen in a lieder recording as much as an opera production, a little too preoccupied with interepreting or telling people what we think about the piece, rather than recreating the piece for it to tell people what its message is. If we are so clever at the end of the twentieth century that we can take pieces that have been heard hundreds of times and literally over one or two hundred years and turn them on their heads and turn them around with different symbols and metaphors that are in the vernacular of our time, it seems to me that we should be able to take that story that is laden with universals that transcend all epochs and make something new out of our own music and our time and our own words, and not start mixing too many contexts, especially when you are dealing with highly epochally centered pieces like da Ponte and Mozart where a blink of an eye or a gesture of a hand means something in a behavioural sense, not symbolically. We should be very careful.

Shooting up was simply not a consciousness and it has nothing to do with the Champagne aria. Is, however, the champagne aria a moment of self-intoxication? Without a doubt. Is it a point where he is actually feeling weak and therefore I got to get a rush because I have a party to go to. Yes, it is about that. Do I read that same Mozartian thing by watching somebody shoot up in a twentieth century setting. I personally don’t in this particular example.

JR: What happens to you when you find yourself in a production like that?

TH: I don’t find myself in a production like that. I did once. It’s not that I am trying to control anything, but I want to put myself only in an environment that I can offer whomever I am working with 125% of Thomas Hampson. I would love to work with these men. I would love to work with Peter Sellars, but I want to work with Peter Sellars when he’s engaging Tom Hampson for something that he thinks that I’ve got the talents to do for and I have the confidence in him to do what he’s going to do. So, we can have dialogue. If there is no compromise or dialogue in the recreation of artistic events, then there is nothing more than ego or, quite frankly, masturbation. As an artist I don’t want to be part of that.

JR: The public is often unaware that some opera recordings are a cut and paste operation where artists record different parts of the work in different cities at different times, or the recording is made and an artist dubbed their role onto it afterwards. Teresa Stratas in Lulu and Cheryl Studer in Carlisle Floyd’s opera “Susanna”. How do you feel about that and what are your feelings on live versus studio recordings?

TH: Live or studio is not really the quesiton. The question is the record. What essential and final, qualitative effect does any of this have on the recording? The recording technical ability today is really quite breathtaking. Frank Sinatra did not sing duets with those people. They phoned it in on ISDN lines. A lot of the music was actually transatlantic cut and paste.

The good news and the bad news of the classical recording industry right now is that the point is to make a record and the record should be of a very high quality. It should realize the work unabashedly and I think this is where the subjective comes in. Therefore, people should only sing on record things that they would in fact sing— a reasonable recreation of themselves.

The idea of cutting and pasting is always negative to the music. You try your absolute level best as an artist to give a serious and continual read of something. I can only control the world that I am involved in. Sometimes that gets compromised for various reasons: illness, technical problems, horrific schedules. Is it more important to say, and in the last analysis do you really care, “oh well this recording doesn’t exactly have the cast that I wanted, but my goodness there are only two cuts in the whole thing in this great, wonderful studio recording”. I don’t think so. People want to hear the people do it.

Certainly the best of all possible worlds is not to cut and paste. To have people come, have them rehearse, have a dialogue, have a relationship, and recreate that: the Walter Legge productions were like that. The lack of rehearsal and the lack of time to work as an entity with the orchestra before the mikes go on because the financial pressure is one of the great shortcomings of the recording industry. They would turn around and say that people can’t hear the difference. I think people can hear the difference. Your question doesn’t have an answer. It is an observation for both sides. The goal has to be the highest quality.

JR: Baroque violinist Reinhard Goebel spent considerable time in the Sächsische Landesbibliothek researching the Augustan Age of Dresden in an attempt to better convey the spirit of 17th century German music and pianist Alfred Brendel has spent a lifetime examining the socio-political and philosophical backdrop of the first Viennese school. I gather that you are also a believer in music in context.

TH: Absolutely. I don’t think that anything in our lives happened in a vacuum. I believe so firmly in interconnectivity in all of the arts, all of the humanities as a basis for the arts. You cannot understand Schumann without understanding Heine. You cannot understand Heine without understanding the Paris of 1840. You can’t understand Paris in 1840 if you don’t know what happened in 1794, ad infinitum. We can’t understand ourselves if we don’t take those things seriously. If we don’t understand why people were willing to die in 1848, we have no right to be as audacious and opinionated as we all are today in 1998. It’s just not fair. It’s irrational. So, I think there is a tremendous interactivity and I don’t think you can understand Mahler’s songs without understanding the basis of Das Wunderhorn or the first-person awakening of 19th century poetry that culminated in an orientalist expunging his personal grief in the name of Friedrich Rückert.

JR: To return to the Net, do you subscribe to mailing lists such as the lieder or opera list and news groups, and if so, do you participate or lurk?

TH: No, I don’t, and when people send threads from them to me I delete them without reading them.

JR: Do you have an opinion of the Microsoft hearings?

TH: No, mine is an emotional one.

JR: Which is?

TH: No comment

JR: What are some of your favourite intenet sites?

TH: Ready for this? The PGA Tour. I am a huge golf nut. I go back and forth and follow some of my friends on the PGA Tour. I tend to do a lot of surfing. I try to get to as many museum sites as I can. I love to see how they handle the multimedia because I would like to design some things.

JR: There are a number of literary references on your website: Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Emmerson, Willa Cather. Are you interested in the rural American tradition? Willa Cather suggests the American Middle West for example.

TH: Absolutely. We wrote the notes to the big Stephen Foster record that I did and the American folksong record that I am planning. Certainly, Willa Cather is going to come up in a big way. I would like to do a Carl Sandburg album in the way that I did the Walt Whitman album, and of course, bring in a lot of early American quasi-folk roots.

JR: It’s quite a contrast, your interest in Central European lieder and American song.

TH: There have been some wonderful new songs from these guys in America. Not just from black composers either. From Jewish, white, whatever. Everybody’s going to this literature and saying “listen to this power, anger, passion, and love”. The wonderful and terribly disturbing poetry of Langston Hughes. I think it would help in the States a lot if we would read each other’s poetry more. You cannot read Langston Hughes and not say somebody was not listening to Walt Whitman. He is wonderful and it’s a wonderful story.

JR: Is racism something you think about as an artist?

TH: I think about it daily. It is one of the most horrifying cancers of our time in every country. Certainly the American racist question is huge. We could have a longer conversation about this. I think I am sensitive to it. I am angered by it. I don’t understand it. I grew up in an environment in the Northwest where we didn’t have it—that kind of animosity: I won’t sit next to that person because he’s a this or that. That was not part of our makeup. I have never understood it and I am appalled by it. And I get physically very angry when I am confronted with it. I would like somehow to participate more in the eradication of it. I think if there’s anything Clinton should be given credit for, it’s approaching and attacking this question on the highest level possible in our country. Bill Clinton may have a lot of problems, but to me he has had more effect in a serious political way of talking about things that really are day to day concerns in our country than any president that I have been alive for. Maybe Kennedy would have gotten to it. I don’t know. I don’t think so. I think Kennedy would have been a disappointment by the end of his term.